How did the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act change personal taxes?

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act made significant changes to individual income taxes and the estate tax. Almost all these provisions expire after 2025.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) made substantial changes to tax rates and the tax base for the individual income tax. The major provisions follow, excluding those that only affect business income.

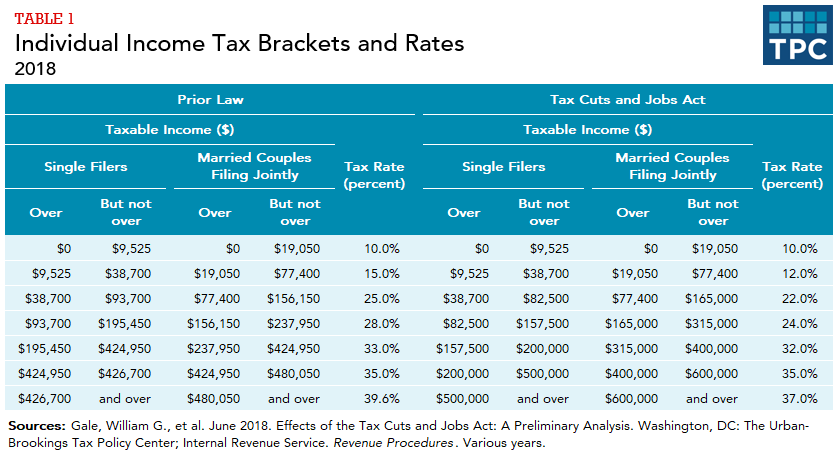

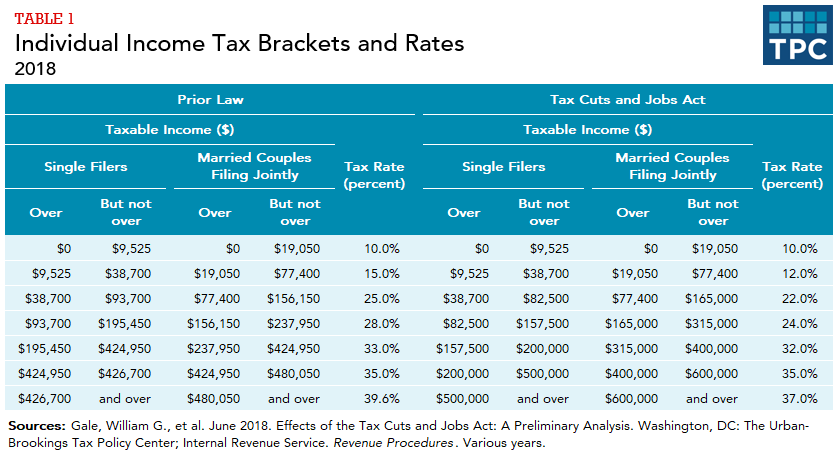

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced statutory tax rates at almost all levels of taxable income and shifted the thresholds for several income tax brackets (table 1). As under prior law, the tax brackets are indexed for inflation but using a different inflation index (see below).

TCJA repealed personal and dependent exemptions. In their place, the law increased the standard deduction and the child tax credit (CTC) and created a new $500 tax credit for dependents not eligible for the child tax credit (table 2).

TCJA expanded the CTC in several ways. It doubled the maximum per child credit amount from $1,000 to $2,000 starting in 2018. It also increased the refundable portion of the credit, but limited the maximum refundable credit to $1,400 per child in 2018. The maximum refundable amount is indexed for inflation, but the maximum total credit amount is not. TCJA limited eligibility for the credit to children who have a valid Social Security Number.

TCJA extended the CTC to higher-income families by substantially increasing the income thresholds at which the credit phases out. As under prior law, the income phaseout thresholds are not indexed for inflation.

The nonrefundable $500 credit for other dependents (not indexed to inflation) applies to:

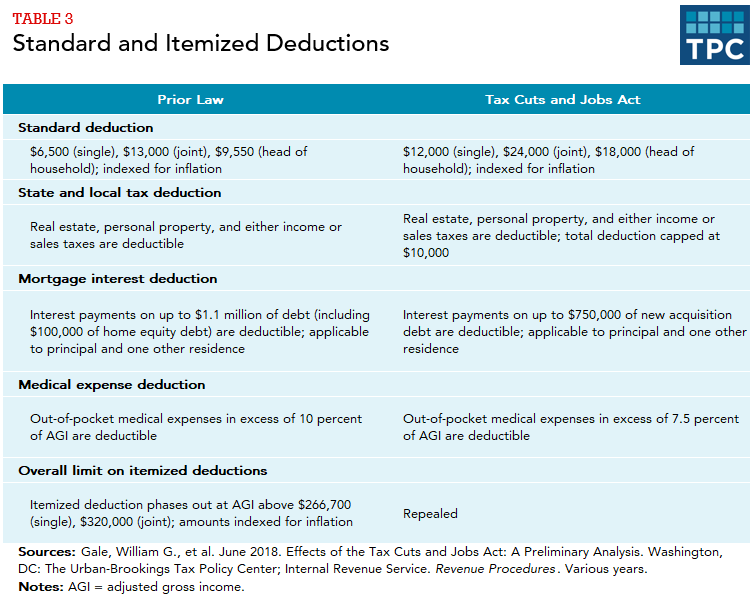

TCJA nearly doubled the standard deduction (table 3). As before, the standard deduction amounts are indexed for inflation. The larger standard deduction substantially reduced the number of taxpayers choosing to itemize their deductions.

TCJA changed the structure of several major itemized deductions. Under prior law, itemizers could claim deductions for all state and local property taxes and the greater of their state and local income or sales taxes (subject to overall limits on itemized deductions). TCJA limited the itemized deduction for total state and local taxes to $10,000 annually, for both single and joint filers, and did not index that limit for inflation. As under prior law, taxpayers cannot claim a deduction for state and local taxes against the alternative minimum tax (AMT).

Under prior law, taxpayers could deduct interest on mortgage payments associated with the first $1 million of principal paid on debt incurred to purchase (or substantially renovate) a primary and secondary residence, plus the first $100,000 in home equity debt. For taxpayers taking new mortgages after the effective date, TCJA limited the deductibility to the interest on the first $750,000 of loan principal and eliminated the deductibility of interest for home equity debt unless used to buy, build, or substantially improve the taxpayer’s home.

Previously, taxpayers could deduct out-of-pocket medical expenses (including costs for health insurance) that exceeded 10 percent of their adjusted gross income (AGI). For 2017 and 2018, TCJA allowed deductions for out-of-pocket medical expenses above 7.5 percent of AGI. Congress later extended the lower 7.5 percent of AGI floor and made it permanent.

TCJA repealed the phase-down of the amount of allowable itemized deductions (sometimes called the Pease provision). This limitation had applied to AGI at or above $266,700 for single filers and $320,000 for taxpayers filing joint returns.

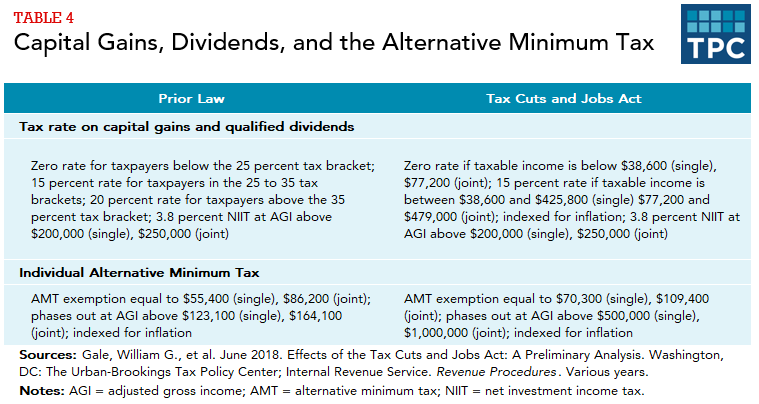

TCJA retained the preferential tax rates on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends and the 3.8 percent net investment income tax (NIIT). The NIIT applies to interest, dividends, short- and long-term capital gains, rents and royalties, and passive business income. TCJA separated the tax-rate thresholds for capital gains and dividend income from the tax brackets for ordinary income for taxpayers with higher incomes (table 4).

TCJA retained the individual AMT but raised the exemption levels and raised the income threshold at which the AMT exemption phases out, which significantly reduced the number of taxpayers subject to the AMT. The exemption amounts and phaseout thresholds continue to be indexed for inflation.

TCJA doubled the estate tax exemption to $11.2 million for single filers and to $22.4 million for couples and continued to index the exemption levels for inflation (table 5). The top estate tax rate remains at 40 percent.

Starting in 2019, TCJA set the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) individual mandate penalty tax to zero. Previously, households without qualifying health insurance were required to pay a penalty equal to the lesser of 2.5 percent of household income or $695 per adult and $347.50 per child, up to a maximum of $2,085. Under the TCJA, individuals who do not enroll in adequate health insurance plans will not face a penalty starting in 2019. Because fewer people obtain free or subsidized coverage in the absence of the penalty, and the reduced costs of ACA premium tax credits and other subsidies and Medicaid benefits far exceed the lost revenue from setting the penalty tax rate to zero, the net effect of this provision reduced the federal budget deficit . This provision does not sunset.

TCJA changed the measure used for inflation indexing from the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) to the chained CPI-U. The chained CPI-U more accurately measures changes in consumer welfare resulting from price changes, because it accounts for people finding substitutes for goods whose prices increase faster than others. The chained CPI-U thus generally increases at a slower rate than the traditional CPI-U. This was expected to reduce the cost of the TCJA because individuals were expected to end up in higher tax brackets and indexed tax credits (like the earned income tax credit) would increase at slower rates than they would have under the old indexing system. However, because the pandemic and the economic recovery changed consumer spending patterns, chained CPI-U temporarily grew faster than traditional CPI-U. The change in indexing is permanent.

A notable feature of the individual tax and the estate tax provisions is that most expire after 2025, except the 7.5 percent of AGI floor for medical expenses (now permanent), zeroing out of the ACA penalty tax, the change in inflation indexing, and several changes in the tax base for business income. In contrast, many of the business tax provisions do not sunset. Congress chose to make the individual provisions temporary to limit the 10-year revenue cost of the TCJA to the amount authorized in the Congressional Budget Resolution ($1.5 trillion) and to comply with Senate budget rules under the process used to pass the tax act and bypass the Senate filibuster, that required no increase in the federal budget deficit after the tenth year.

In 2022, TPC estimated that making the individual income tax provisions of the TCJA permanent would cost about $3 trillion over a decade. All households would see their after-tax income increase under such a scenario, but the increase is larger as a percentage of after-tax income for those in the top 20 percent of the income distribution.